One of my favorite places in the whole damn world is Museum Campus on Chicago’s lakeshore, specifically the area around the Field Museum and the Shedd Aquarium. On occasion, usually when the weather is good or I have time to kill or just feel the need, I’ll walk down along the walking and biking paths in the area, the ones that wrap down around the back of the aquarium, whose edges drop straight down into Lake Michigan. Sometimes they’re closed off because of ice or because the waves on the lake are too high, making them dangerous to walk. Sometimes even when they’re open, you’ll get sprayed by water from a freshwater sea that isn’t as the waves crash against the edge of these pathways.

It’s one of those places that I sometimes wonder if visitors ever think to wander along, or if it tends to be the provenance of locals, who bike along it in their lane, take their morning runs along the slanting walkways and the quiet that can come in those spaces, especially before the day really begins. The view is really spectacular, even on misty days when the fog hangs heavy over the water and you can’t even see the park a few hundred yards away. Of course, maybe I’m biased. It is, after all, one of my favorite places, and I know that if I lived in the city I’d be there as often as I could be, convenience be damned.

Another point in favor of my eventually moving there, I guess.

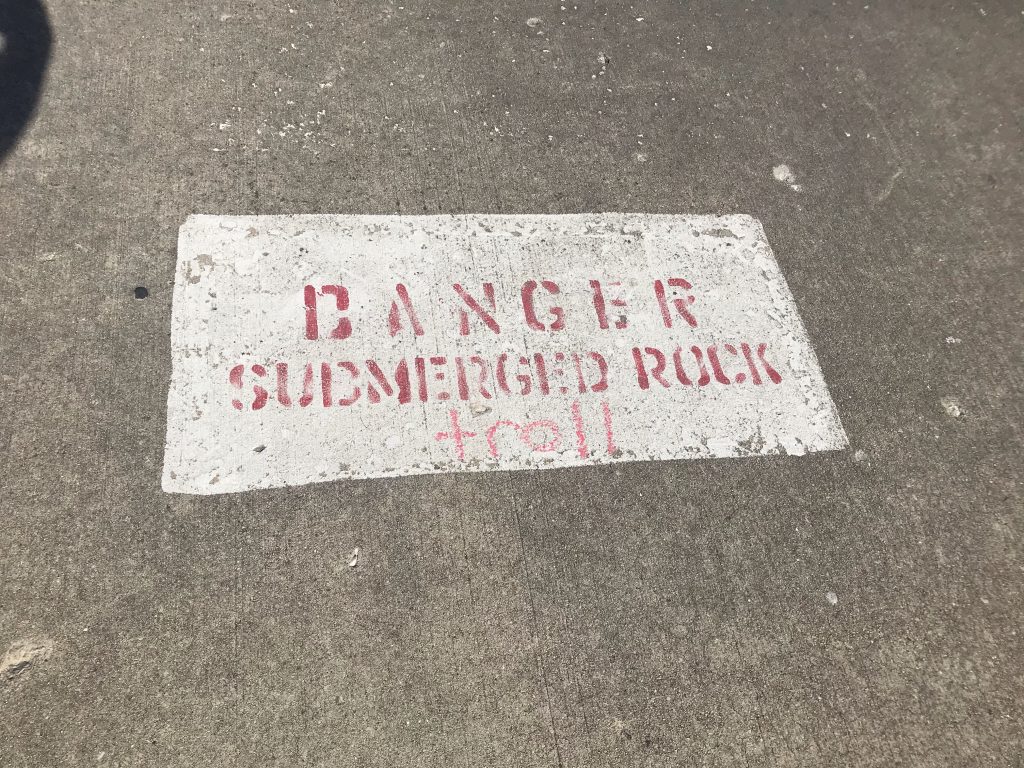

Along one of those pathways are old warmings painted onto the pavement, telling passersby—and anyone who might consider jumping into the water—that there are submerged rocks in the area along the shore. On the one hand, it seems silly that the warning would be needed. It’s not a beach, not a swimming area, but there are certainly folks who fish along that pathway amongst the runners and the cyclists and wanderers. The warning would be as much for them, who could lose a line in those rocks, or anyone who falls in or would-be rescuers.

Five years ago while walking the pathway, I snapped a picture of one of those warnings. Someone with a sense of humor and a touch of whimsy decided to add a bit of extra flavor to one of those warnings. I haven’t been back in the last year or so to see if it’s still there or if it’s been repainted, but it was still there a few years ago, the last time I was able to come down while the weather was good enough to wander down toward the water.

I’ve wondered since the first time I saw it—it’s been there for a lot longer than five years—about whoever painted the word “troll” onto that warning. A college kid on a dare, a nerdy one out with friends? High schoolers out for a laugh? A creative with a penchant for a little bit of graffiti?

There’s a story behind it, one I know that I will never know. Somehow, though, that makes it that much more interesting, that much more magical. A touch of whimsy to the mundane, something that exists if you’re willing to find it. That’s a little something we all need, now more than ever. A little touch of magic to a gray, hard world.

So here’s to the magic makers and those who seek it—the ones that make joy and those who find pleasure in what’s been made.